Welcome to tipsday, your opportunity to reward yourself for making it through Monday and stock up on informal writerly learnings.

Greer Macallister wonders if authors should review books. Then, Jim Dempsey discusses the inherent nature of story structure. Juliet Marillier charts the ups and downs of a writer’s journey. Later in the week, Julie Duffy wants you to choose your own adventure. Then, Kelsey Allagood shows you how to be creative when you’re feeling “blah.” Writer Unboxed

Jill Bearup analyzes the Loki ep. 6 fight scene.

Richelle Lyn explains how Creativity, Inc. inspired her. Later in the week, Rachel Smith reveals how to use sensory details in historical fiction. Then, F.E. Choe shares five tips for navigating writing events as an extreme introvert. DIY MFA

Lindsay Ellis reveals the unappreciated women writers who invented the novel. It’s Lit | PBS Storied

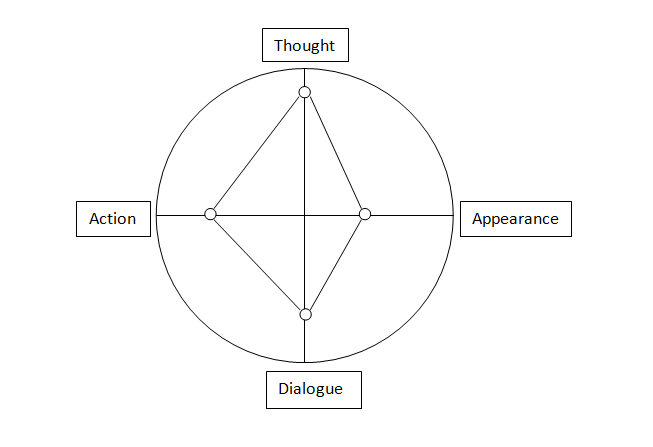

Janice Hardy offers some advice. Do, or do not. There is no try. Clarifying what your characters do. Then, Kristin Durfee explains how to plot your way back from an unruly idea. Later in the week, Rayne Hall considers 12 story ending twists that don’t work. Fiction University

Why we can’t save the ones we love. Like Stories of Old

K.M. Weiland provides a summary of all the archetypal character arcs. Helping Writers Become Authors

Lisa Hall-Wilson helps you write complex emotions in deep POV: shame.

Alli Sinclair wonders, what is your character’s love language (and why does it matter)? Writers Helping Writers

Why there are so many lesbian period pieces. The Take

Kristen Lamb explains why editing matters (and simple ways to make your work shine). Then, she’s spotting terminological inexactitude syndrome.

Nathan Bransford advises you to avoid naming universal emotions in your novel.

Kathryn Goldman answers the question: are fictional characters protected under copyright law? Then, Jessica Conoley points out the most significant choice of your writing career. Jane Friedman

Why Disney kids take over everything—corporate girlhood. The Take

Eldred Bird presents five more writing tips we love to hate. Writers in the Storm

Chris Winkle explains how Romanticism harms novelists. Then, Oren Ashkenazi examines how Michael J. Sullivan employs the Neolithic in Age of Myth. Mythcreants

Award-winning speculative fiction author (and Damon Knight Grand Master) Nalo Hopkinson joins UBC creative writing faculty. I may just have to invest in another degree! UBC

Thank you for stopping by. I hope you took away something to support your current work in progress.

Until Thursday, be well and stay safe, my writerly friends!